Electricity generation from clean sources: Key solution to achieve net-zero emissions

Carbon credits are permits that allow the holder to emit a specific amount of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases (GHGs). One credit permits the emission of one ton of carbon dioxide or an equivalent amount of other greenhouse gases.

The carbon market was established as a result of the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. According to the Protocol, countries that have not reached their emission limits can sell their excess allowances to those that are emitting gases above the thresholds.

Carbon markets have been heating up recently (climate change pun intended) due to new regulations, the increasing number of emission trading systems, and the growing interest in providing retail investing options. This article will present information on the types of carbon markets and how to invest in them.

Carbon market

Carbon markets were created to provide carbon offsets, credits, or allowances that are measured in metric tons of carbon dioxide or equivalent. One credit equates to the reduction, sequestration, or offset of one ton of carbon dioxide or the equivalent amount of different greenhouse gases. These gases include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6).

The Two Types of Carbon Markets

There are two types of carbon markets, two very different systems are often mistakenly merged. One is mandatory, the other is voluntary, and they operate very differently.

The voluntary carbon market (VCM), in which individuals, corporations, or governments can voluntarily purchase carbon offsets/credits or invest in projects that mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Voluntary offset buyers are often driven by certain considerations such as safeguarding their reputation, ethics, and corporate social responsibility. For example, some companies offer their customers a carbon offset up-sell related to their products or services, such as airlines like American Airlines, Delta, and United Airlines. Other companies, such as Xerox and Walmart by 2040 and Microsoft and Apple by 2030, are choosing to become carbon neutral. They are working towards this goal through investments in projects and/or purchases of carbon credits.

The voluntary carbon market is much smaller than mandatory carbon market. The real value of the voluntary carbon market was around $2 billion in 2022 [1]. The voluntary market is not regulated, is opaque, and can be difficult to verify. A company may choose to offset as little or as much of its pollution, and the efficacy of the offset can be challenging to confirm.

Additionally, Puro.earth, the world’s leading carbon crediting platform for engineered carbon removal, aims to help companies globally in their science-based journey to net-zero by connecting them together with suppliers of carbon net-negative technologies. They enables climate-conscious companies to neutralize their emissions with CO2 Removal Certificates (CORCs), a revolutionary new carbon removal credit (disclosure: Nasdaq owns a majority stake in Puro). This process begins with Puro.earth identifying suppliers with negative net emissions, meaning they remove more carbon from the atmosphere than they emit. The sequestered carbon is then scientifically measured and independently verified by a reputable third party. After accounting for the supplier’s own emissions, only the net negative emissions are turned into CORCs. Once issued, companies can purchase these carbon removal credits from accredited suppliers or a Puro.earth partner to offset the carbon emissions they could not avoid or reduce.

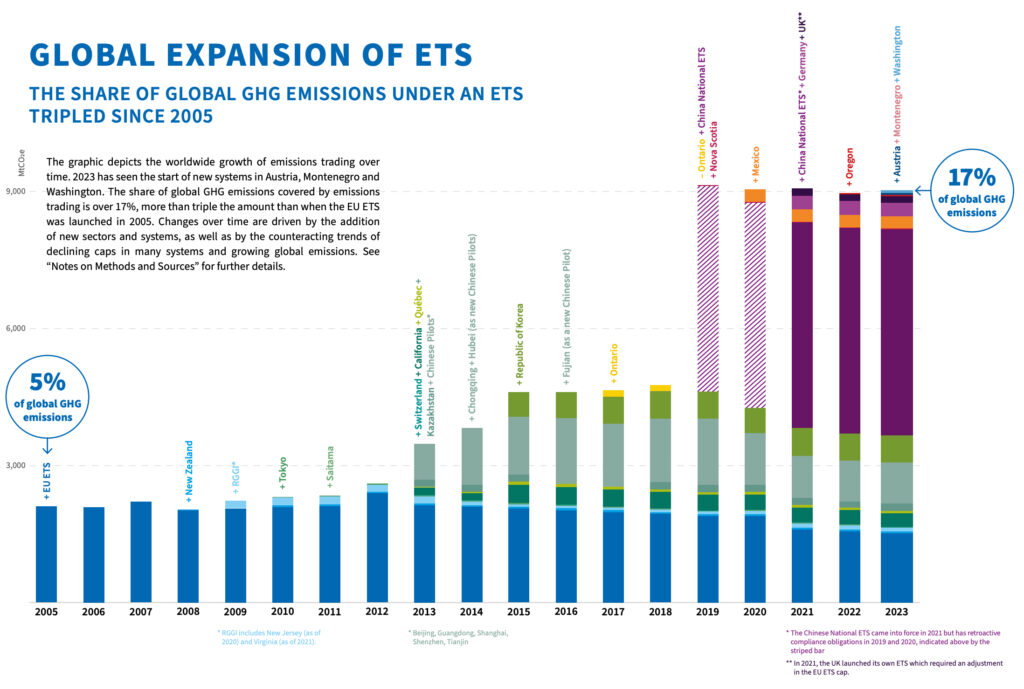

The mandatory carbon markets: Mandatory carbon markets referred to as Emissions Trading Systems or ETS. This market utterly dwarfs the voluntary carbon market, with governments globally raising a record of over $63 billion from the sale of carbon allowances in emission trading systems in 2022. As of 2024, 36 ETSs are operating globally [2]. These market includes the EU Emissions Trading System (EUAs) and schemes in Mexico, California, Oregon, Washington, Quebec, the United Kingdom, Kazakhstan, Japan, and China….These system covers 17% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Global expansion of ETS is shown in the graphic.

(Source: https://forestcarbon.forestry.ubc.ca)

The graphic depicts the worldwide growth of emissions trading over time. Systems are spreading around the world. With new additions in Austria, Motenegro and Washington in 2023, the share of GHG emissions covered by emissions trading has tripled since the launch of the EU ETS in 2005.

The purpose of the market is to reduce pollution by reducing the annual supply of allowances every year through 2030. It is a regulated market with high visibility and is easily verified.

How does an Emissions Trading System (ETS) work?

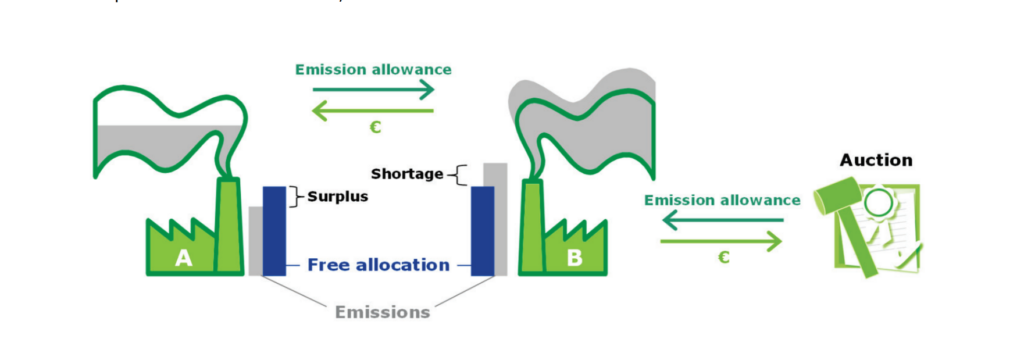

ETS are created by governments, setting a cap on how much CO2 can be emitted. ETS controls emissions from facilities by allocating emission allowances. Emitting facilities under ETS have the right to trade these emission allowances with each other to optimize the cost of reducing emissions. If they fail to cover emissions with allowances, firms must pay a penalty.

The ETS operates on the ‘cap and trade’ principle. A cap is a limit set on the total amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted by the installations covered by the system. The government sets an emissions cap and issues a quantity of emission allowances consistent with that cap (one allowance gives the right to emit one tonne of CO2eq – carbon dioxide equivalent). The cap is reduced annually in line with the climate target, ensuring that emissions decrease over time.

Each year, some allowances are given to the companies by the ETS for free, but if a company pollutes more than the allowances given, it needs to buy more in the allowance auction market.

(Source: EU ETS Handbook)

To understand how an ETS works, let’s examine the European Union’s ETS, which like all ETSs. The EU ETS currently covers emissions from over 10,000 power plants and factories in the EU, energy-intensive heavy industries (such as oil refineries and producers of iron, aluminum, cement, and paper), and airline flights within the EU. From 2013 to 2020, around 43% of total allowances were allocated to companies for free. The manufacturing industry received 80% of its allowance for free in 2013, which decreased to 30% by 2020. Most power generators receive no free allowances and must purchase all of their needs, with exceptions in a few EU member states..

Every year on April 30th, industries in the EU under the scheme must deliver to their government the same number of EU Allowances (EUAs) as tons of carbon they have emitted over the prior year. If they fail to do so, the fine is €100 per excess ton, but it doesn’t end there: the company must deliver EUAs for the uncovered emissions in the following years. So, if a company is short 200 EUAs, it will pay a fine of €20,000 and must deliver an additional 200 EUAs the following year on top of enough EUAs to cover that year’s emissions.

The EU ETS has a significant impact on greenhouse gas emissions, reducing about 2-4% of the total capped emissions, which is much bigger than the impact of most other individual energy-environmental policy instruments. In addition, the EU ETS can attract business paying attention to climate change and has an impact on investment orientation, contributing to prevent investment in high-carbon sectors and shifting towards low – carbon investments.

The table below will show differences between the mandatory carbon market and the voluntary carbon market.

| The mandatory carbon markets | The voluntary carbon market | |

| Compliance | The markets are created and regulated by mandatory national, regional, or international carbon reduction regimes | Enable companies and individuals to purchase carbon offsets on a voluntary basis and they are often driven by certain considerations such as safeguarding their reputation, ethics, and corporate social responsibility. |

| How does it work | Referred to as ETS, allowances are allocated or auctioned to companies, which can then be traded with each other; If a company’s emissions of GHGs exceed the free allowances they were given at the start of the year, they can buy allowances from auctions or from other participants who have reduced their emissions and hold surplus allowances | Through investing in projects that prevent, reduce, and remove greenhouse gas emissions including Afforestation, forest management, renewable energy, wetland restoration, etc. |

| Exchanged Commodity | Allowances. Facilitated by the cap-and-trade system. | Carbon offsets. Facilitated by the project-based system |

| Who can purchase credits? | Companies and governments have adopted emission limits established by the United Nations Convention on Climate change | Businesses, governments, NGOs, and individuals |

| Characteristics | Much more significant market

It is a regulated market with high visibility and is easily verified the through the allowances |

The much smaller

The voluntary market is not regulated, is opaque, difficult to verify |

Overall, there are fundamental differences between mandatory carbon markets and voluntary carbon markets, although both markets play important roles in achieving a low-carbon economy. The mandatory carbon markets operate on mandatory framework. Meanwhile, the voluntary carbon markets work on a voluntary basis. For governments, mandatory carbon markets are vital in achieving carbon reduction targets. However, these markets complement each other, making it easier for buyers who need to achieve carbon offsets for their day-to-day operational activities.

Impact of New Regulations

In mid-2021, the European climate law came into effect, which increased the binding target of net greenhouse emission reductions by at least 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels) versus the previous target of 43%. In December 2022, the European Parliament, member state governments in the EU Council, and the European Commission reached a deal to reform the existing Emissions Trading Systems and to add an additional system for transport and heating fuels. Whereas the overall number of emission allowances was previously set to decline at an annual rate of 2.2%, the new reduction factors are 4.3% from 2024 to 2027 and 4.4% from 2028 to 2030. In addition, shipping industry emissions are to be included, and the free allocations to aircraft operators are to be phased out. The bottom line is that the supply of allowances is now set to decline at a faster pace, and the demand for mandatory allowances is expanding. [3]

Between 2021 and 2030, the overall number of emission allowances was previously set to decline at an annual rate of 2.2% to cut all greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% from 1990 levels by 2030.

The law aims to put climate at the heart of all EU policymaking, ensuring that future regulations support the emissions-cutting aims. Doing that will require a huge policy overhaul. The proposals will include EU carbon market reforms, tougher CO2 standards for new cars, and more ambitious renewable energy targets. Besides, ETS are also required to work more effectively to lower allowances. Climate law also requires Brussels to launch an independent expert body to advise on climate policies, and a budget-like mechanism to calculate the total emissions the EU can produce from 2030-2050, under its climate targets.

How can you invest?

Much of this voluntary market is project-driven, and most of the offerings are about investing in without having an intention to or path to cashing out. However, in recent years Wall Street and industry players have been working to make the voluntary system more accessible. These are some of the companies operating in the space:

Futures exchanges exist to facilitate transactions for spot and future deliveries of allowances. Trades can occur between two willing companies, people, carbon brokers, or in the options markets. Individuals can purchase carbon-credit futures in much the way investors can purchase futures in general, but an easier strategy would be to invest in ETFs, futures exchanges such as KraneShares Global Carbon Strategy ETF (KRBN) , KraneShares European Carbon Allowance Strategy ETF (KEUA), KraneShares California Carbon Allowance Strategy ETF (KCCA), the iPath B Carbon ETN (GRN), the Kakubi token (KKB) [4]

Carbon trading markets are designed to allow for the buying and selling of the right to emit a ton of CO2 (or equivalent). providing many options and opportunities for businesses and investors in the carbon markets through projects, companies, and funds operating in this field.

Vietnam’s carbon market

Vietnam has developed legal corridor on carbon credits and carbon credit transactions in Vietnam: Law on Environmental Protection 2020 (Article 139 – Organization and development of domestic carbon market), Decree No. 06/2022 /ND-CP regulates mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and protection of the ozone layer, Decision No. 01/2022/QD-TTg issued a list of sectors and facilities emitting greenhouse gases that must carry out greenhouse gases inventory, whereby 1,912 facilities will be able to participate in the domestic carbon market. Circular No. 17/2022/TT-BTNMT provides methods for measurement, reporting, appraisal of reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and GHG inventory development in waste management.

By issuing the regulation on carbon market, it shows that the domestic carbon market is gradually being shaped more clearly.

Vietnam has received a 51.5 million USD, equivalent to 1,200 billion VND payment for verified emissions reductions – commonly referred to as carbon credits according to the Emission Reductions Payment Agreement (ERPA) in the north-central region was signed between Vietnam (the MARD) and the World Bank.

In Vietnam, the establishment of a domestic carbon market is expected to help Vietnam archiving its net zero goal by 2050. It is expected that a carbon credit trading floor officially operate by 2028. In Vietnam’s agricultural sector alone, experts estimate that it can generate 57 million carbon credits per year, helping the country earn nearly $300 million a year. [5] This shows that Vietnam has great potential for carbon market development. However, Vietnam needs to conduct more research and develop mechanisms and policies to participate in the global carbon market and contribute to economic development as well as archive greenhouse gases emissions reduction target.

References: